The sound of my alarm echoed against the thin walls of the cramped hostel room. Still in a daze, I grabbed my backpack which I had carefully packed the night before, took my camera out of the locker, and squeezed on my sneakers.

In the early hours of this Wednesday morning, I walked along the cobblestone streets of Prague, taking special notice of the blocks that glistened having recently been washed by diligent store owners. Life was emerging from its slumber.

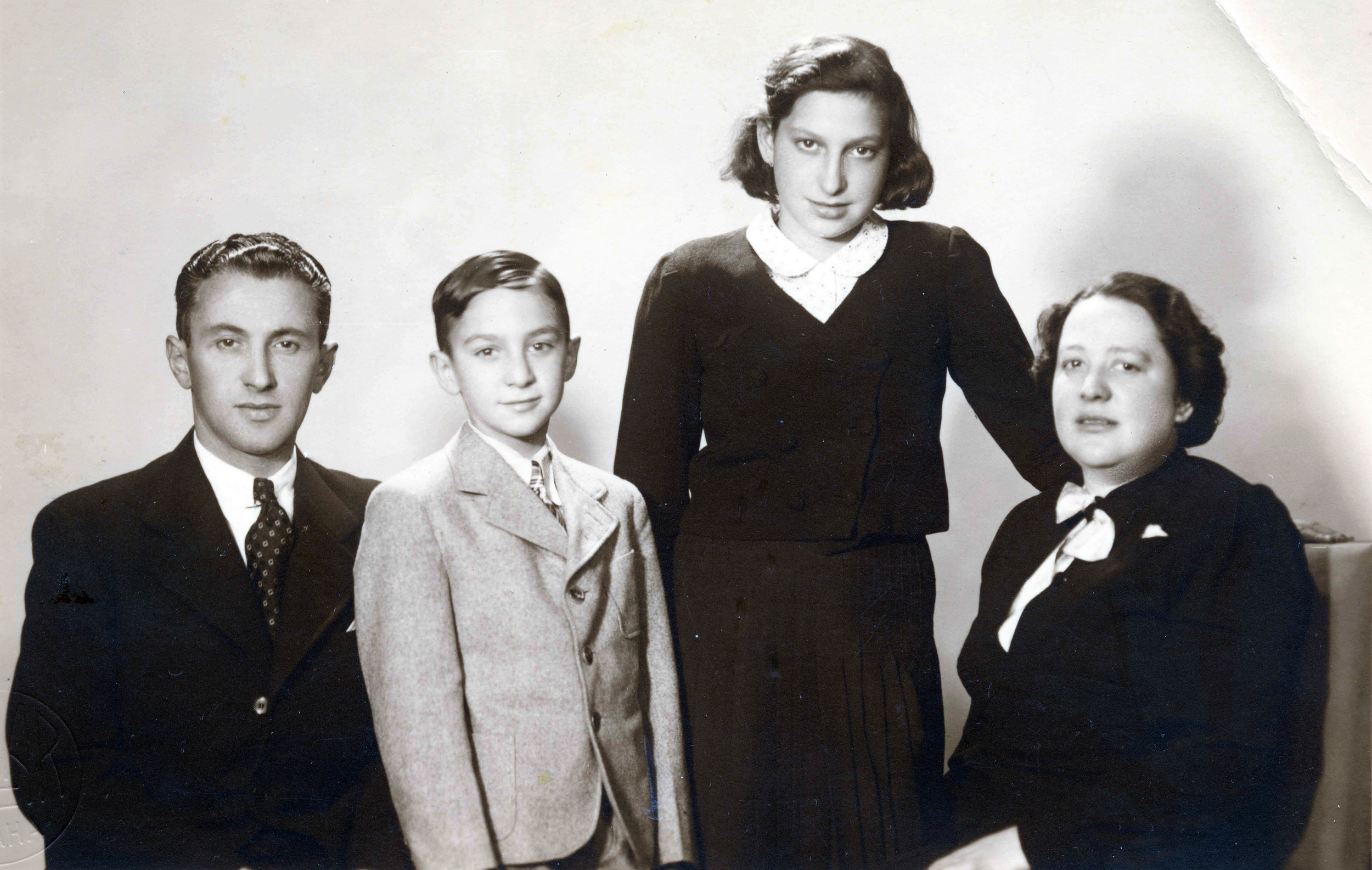

One of the last family portraits taken of Hana with her family and her younger brother, Petr / 1939

It wasn’t more than 20 minutes before I arrived at the Prague Main Railway Station. I first approached the part of the building that remained from the prewar era. I took a few photographs before heading underground to be greeted by a swarm of commuters and travelers. I blended in. No one knew if I was Czech or American, whether I was coming or going, or if I had slept well or been up all night. It was almost as if I didn’t exist. I was just another body to avoid bumping into.

I stood on the platform with nothing more than the clothes I was wearing, a couple of camera lenses, a tripod, and a journal. My thoughts bounced between the notion that 75 years ago my grandmother stood at the same station, hugging her family for the final time, and my curiosities regarding what would come from the next few days.

The first train I boarded took me from Prague to Berlin. There is no doubt that it was more comfortable than the one that my grandmother took in 1939. I had a cozy compartment all to myself and there was a restaurant cafe in case hunger struck. The railroad employees were perfectly friendly and became especially helpful upon hearing my obvious American accent. Now, in the year 2014, when traveling from the Czech Republic to Germany, it barely feels as though you are crossing an international border. Both countries are part of the Schengen Area which is comprised of 26 European nations who have done away with any type of border control when passing from one to another. For much of recent history, this convenience was the furthest thing from reality. In her reflection piece, Stepping Stones In My Life, Hana wrote, “… I sat alone on the train for hours, crossing different countries. Papers being examined by passport control’s sourly officials, giving me dirty looks, stamped and handed back to me with a sneer.”

As the train chugged along, the scenery changed from Prague’s urban beauty to the scenic view of rural Czech Republic. And then, without warning, the signs were in German and the houses looked a bit different. The landscape was lovely, a reminder of the fleeting fall season as many yellow and orange leaves still clung to their branches.

As we neared Berlin, I began to think about some of Hana’s experiences and tried to envision how I would react if I had been in her place. When she transferred trains in Germany, the country which had just recently invaded her own, taking away her nationality and her childhood, she was forced to strip naked and had her most private of places searched in case she was smuggling jewels, an item illegal for a Jew to own at that time. She was freshly 14 and still under the impression that kissing a boy would leave her pregnant. She was innocent and she was naive. She was just a young girl.

My next train took me from Berlin to Rostock and from there I switched to a local train that took me to my final destination for the day, Warnemunde. During this ride, as the sun started to set, I began rereading some of Hana’s writings. I read parts of her diary from 1939 when she had just left home, journals from the 1980s after she had gone through a divorce, a letter she wrote to me in 1992 when I was three years old, as well as reflection pieces that she wrote during the final 10 years of her life.

All of a sudden, these words, which I already knew well, felt different. I couldn’t digest them in the way I did reading them from the comfort of my bedroom in Boston. They settled in my soul and sank into my subconscious.

Upon arriving in Warnemunde, the smell of the sea surrounded me and the cool breeze that only comes from a coastline brushed against my skin, softening my mood. I woke up to the same darkness to which I fell asleep. I was anxious to get to the shore; the waters of the Baltic Sea were the reason I was here.

I exited the hotel and within a couple of minutes, I was stepping on sand. The air was warm enough for comfort, but cool enough that I was cozy in my wool socks. The sky was cloudy and the wind whispered in my ears, letting me know it was responsible for the subtle, yet persistent waves.

I stayed there for a bit over an hour. I set up my tripod and photographed the gentle sky. Slowly, moving with the speed of the rising sun, I made my way closer and closer to the tide. Eventually, I took off my gloves and let my fingers graze the sea. These waters were responsible for carrying my grandmother to safety.

Once daylight arrived, I had to make my way from Warnemunde to Rostock to board a ferry to Denmark - the next phase of this journey.

A sweet older woman, dressed from head to toe in purple, stood near me at the bus stop. In hopes of confirming my travel route, I asked her if I was going in the right direction. She spoke no English, but by using basic hand motions, an impromptu drawing of a ship, and names of stations, she was able to understand my question. She said yes, but expressed serious concern and began rapidly speaking to me in German in hopes I would spontaneously learn her language.

Once on the bus, she patted the seat next to her, signaling for me to sit down. She started discussing my problem with the bus driver which seemed to be a bigger issue than I realized. She talked to strangers, then she talked to me. I still didn’t understand. Eventually, with all of her energy and enthusiasm, she acted out a union strike as if it were the final round of charades and we were about to win a big prize.

She eventually found a teenage boy to translate to me that I should stay with her. I followed her onto another bus, a local train and then for a fifteen minute walk through town. During this time, we didn’t talk. We couldn’t. But, we would occasionally exchange smiles confirming our companionship.

Once arriving to where I needed to be, she gave me a warm hug before turning and walking away, the sound of her purple high heels clacking against the pavement. We never exchanged names nor the reason for my travels. She let me take her picture and I will forever remember her face as one that added great meaning to my travels.

In 1943, when Denmark was no longer safe for Jews, a man came to the family that Hana was working for, and asked if they had a Jewish girl living there. They said yes and brought her to him. He asked if she had a bike. When she nodded, he told her to follow him. He lead her to a church where she would hide in the bell tower for three days before escaping to Sweden, packed underneath herring on an illegal fishing boat.

That was not the first, nor the last time her life would be saved by a stranger.

I am not a victim of war, as too many people are today. And, in an emergency situation, I have a credit card that could pay for a cab or even a plane ticket out of an uncomfortable or unsafe situation. But, not succumbing to that method of escape in my moment of confusion was an important reminder of how much can come from the kindness of others.

I made it to the Rostock Port before noon and bought myself a ferry ticket for seven euros, about nine American dollars. As I boarded this ship, I felt like a little kid. I explored from the top to the bottom, peeking into places I probably shouldn’t have. The ride was just shy of two hours. We approached the Danish shores to the sun setting in the distance. The sky remained grey as it had been in the early morning. And the air was still chilly, but not yet cold.

In 1939, upon arriving in Gedser, Hana boarded a train that took her to Copenhagen. That train station closed in 2009, but I was able to take a bus to one nearby. As I stared out the window, I became enchanted by the landscape. It was beautiful – flat, green and lush. The clouds hung so low, that I felt compelled to reach up into the sky and grab a handful as if it were cotton candy. The quaint houses could have been plucked out of any Hans Christian Anderson fairy tale.

I imagined how she must have felt - from land to sea and from sea to land. From the comfort of home and a loving embrace to strangers and blind faith. From an urban life filled with castles and streetcars to miles of undeveloped countryside. From an education that consisted of three different languages to physical labor that included feeding chickens and milking cows. There was no one there to coddle her and nothing to look forward to.

Once I arrived in Copenhagen, I checked into a youth hostel for the night. I was up before six to make it to my flight back to Prague. It took me two days to get to Denmark and just one hour to get back to my new home in the Czech Republic.

In 50 hours, I navigated 3 countries by boarding 7 buses, 7 trains, 1 international ferry and 1 airplane. The journey exhausted me – physically, mentally and most of all emotionally.

The more I learn about my grandmother’s life and what she endured during her journey to find a stable home, the more in awe I am of her strength and ability to not just adapt, but to thrive. I can’t help but think about the millions of people who are displaced today – children, mothers and fathers, husbands and wives, brothers and sisters, and friends – good hearted people who have been forced to flee the simple comforts of life for no reason other than the fact that they were born into their culture at the wrong time in history.