It is another world over here – a world where I know the language and am comfortable with the currency, a world where the recent federal court ruling regarding gay marriage is celebrated with incredible enthusiasm, and the hurt of the horrible June 17th shooting in Charleston stings the soul. I am back in America.

I am in an unfamiliar America. I am in Cincinnati, Ohio – nearly 800 miles from my home of Boston, Massachusetts. I don’t know the layout of the city nor am I completely sure whether to define this place as the Midwest or the South as I keep getting competing answers from locals. Regardless, I am truly surrounded by the friendliest and most engaging people I have met while retracing Hana’s displacement.

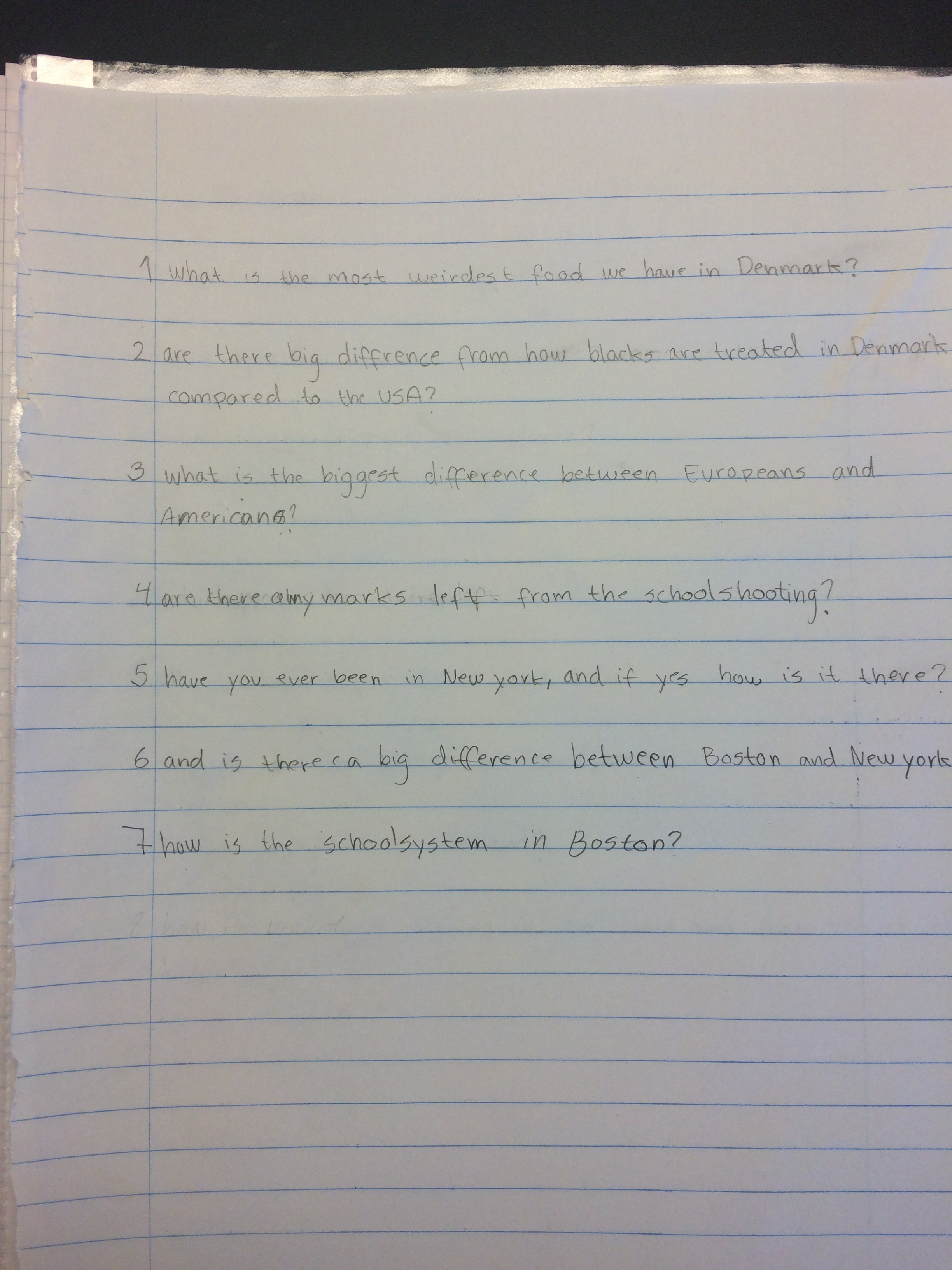

I have had to speak to the culture of my country in Europe, but confronting social issues from afar is an easy task. When I was in Denmark, I would on occasion visit the small school in the countryside near where I was living. One of the teachers asked me to speak with her ninth grade class and if the students could ask me questions about life in America. Aside for the basic curiosities, such as if I liked eating oats and if I followed futbol (soccer), I was asked about racism and gun violence – topics that caught me off guard, embarrassed me and seemed like an overwhelming task to address.

These questions have stayed with me and reemerged as I began my travels across the United States. Hana immigrated to America in 1950, having received an affidavit that her father had applied for when the war had just begun. She recounted in her oral narrative, “Back in the 1930s, people still could get out of the occupied countries, but nobody wanted us. You couldn’t just cross borders unless you had a connection and a guarantee that you would not be a burden to the people or the authorities. So when the papers came to my parents and to me, it was too late. I don’t know anything about if my parents even saw the papers, they may have been dead. But, I got the papers.”

Hana’s very distant connection was the stepsister of her grandmother. The head of the family was named Rudolph Weil and they owned a bakery.

Her story in Cincinnati begins with the an acknowledgment of how little she understood about the culture that existed in America at the time, specifically racism. “I came here around Thanksgiving in 1950 and I really didn’t know much about the prejudices in the United States towards black people. The first first black person I saw was in Stockholm. His name was Mr. Mosley and he was from Frankfort, Kentucky. And when he found out that I was going to go to Cincinnati, Ohio, he asked if I wouldn’t mind taking a package along for his family. I got to Cincinnati about 4 weeks later.”

After several weeks of living with her distant relatives, Hana got up the courage to ask to use their phone in order to call Mr. Mosley’s family so she could deliver the gifts to them. In a piece of writing from 2005 titled “My First Encounter with Racial Prejudice", Hana wrote :

“They had a party line, which means the same number to two or three different households (yes it existed at that time in America, but not Sweden). Their line was shared with their married daughter, who listened on my conversation and told her parents that I dialed a number which was probably in the black ghetto. I asked the person who answered the phone to come and pick up the packages and he replied, “Oh, no, I cannot do that. Why don’t we meet in center square. You’ll recognize me wearing a green hat.” I gave it no thought why he didn’t want to come to the neighborhood I lived in. When the day came, Joe, their son was assigned to accompany me on the bus. We arrived at the agreed upon place in the square and I saw a man with a green hat and went over to him. He was black. He thanked me profusely for going to so much trouble and informed me that his parents would be honored to have me for dinner. I was pleased to be invited. Joe exploded, “You are not going with a Nigger anywhere.” I said I would. He slapped me right then and there and I was more furious and went with Ken to his parents house. The father was a Pullman porter at the Baltimore-Ohio railroad. The house was immaculate. It was also the first time I encountered plastic slip covers on top of slip covers. The meal was delicious, the conversation halting with my poor English, but they were curious about life in Sweden. After dinner Ken took me to my bus stop. When I arrived back at my house, my two suitcases were in front of it with a note, ‘We do not harbor Nigger lover’.”

There are many things I admire about the woman that my grandmother grew to be, but this story is perhaps the best example of why her life has inspired me to take this journey and dedicate myself to understanding her history. She had this streak of independence guided by her morals and her understanding of what felt right and what felt wrong. When she shared this story with me back in 2010, just months before her death, she said, “So now I ask you, someone who has never met me in Denmark rescues me during the war. And, then someone who is vaguely related to me in Cincinnati, who knows all about the Holocaust and what I went through, kicks me out because I met a black man on the square. That is what I had come to America for? And I now I sit here with my beautiful granddaughter on my death bed…”

The Weils left her in the middle of a winter night with nothing more than her personal belongings and the $200 that her father had sent when applying for the affidavit. She walked through the night with the words ringing in her ears, “If they found out that you talked to a Nigger on the party line, they will burn our house down.”

After wandering the streets, Hana eventually found a room for rent in a three-story house and with that, the second chapter of her life in America began.

Due to Hana’s understanding of the significance of her own personal history, I was able to find her Cincinnati addresses and went to find these residences, both near the Avondale neighborhood. This part of the city and the surrounding area used to be predominantly Jewish and home to many German immigrants. In the 1950s, there was a cultural shift that can only be described as “white flight.” Most of the Jewish families moved to the surrounding suburbs and African American families moved in. Unfortunately, due to the racial divide, current events, and the lack of opportunities for the new residents, the community had a downward spiral of wealth and safety.

I went into these neighborhoods to search for her two homes. I took a bus to the second residence first and after talking to some individuals who work nearby, learned that the address I was searching for no longer existed. At some point, the building must have been torn down. I took a cab to the second address and in the pouring rain stood on the stoop where she had once again faced that fact that she was entirely on her own. I wonder how different she felt at this moment than the instance when she landed on the shores of Sweden just a short seven years before.

Hana lived in Cincinnati for a little less than a year. She got a job at Red Feather Agency, now called United Way, that served underemployed and under privileged people and was assigned to a speech and hearing center, making $32 a week. Each success was paired with a cultural challenge, often times having to do with the nuances of the English language. “One day a women calls up. My English was getting so good that your hair didn’t stand up on your head when I spoke. I thought I spoke perfect. This women said, I am sorry I have to cancel my husbands appointment because he passed away. I said, where did he go to? She kept saying he passed, he passed, he passed. I didn’t understand. So she asked to talk to my boss and he said, “she is just a dumb immigrant.”"

In the mean time she met Ralph Seckel, a German-Jewish immigrant at a picnic held between Cincinnati and Dayton, Ohio. Ralph and Hana struck up a relationship. “Ralph started talking to me. He said that there was an opera on the radio, would you like to come and listen to it in my car. In Europe I was always told never to go with an American in his car. I told him this. He told me he would keep all 4 doors open. I said okay.”

Her relationship with Ralph was complicated and although she would end up marrying him, it would be jumping ahead in this story to go on about that. Hana, being content, but not satisfied with her life in Cincinnati, dreamed of San Francisco, “In Europe, I always heard about earthquakes in America. The last earthquake I knew was San Francisco in 1912. I wanted to see how it looked after the earthquake. So, I saved money and said goodbye to my job and went.”